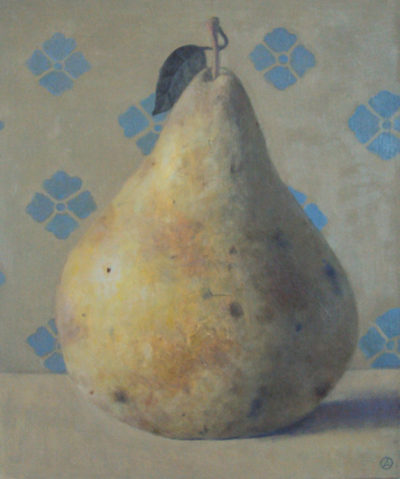

Stilled Life

Stilled Life

“I have fallen in love with a painting. Though that phrase doesn’t seem to suffice … rather it’s that I have been drawn into the orbit of a painting, have allowed myself to be pulled into its sphere by casual attraction deepening to something more compelling. I have felt the energy and life of the painting’s will; I have been held there, instructed … The result of looking and looking into its brimming surface as long as I could look, is love, by which I mean a sense of tenderness toward experience, of being held within an intimacy with the things of the world.”

–Mark Doty, “Still Life with Oysters and Lemon”

Everything moves.

The world zips and flickers past us unbound, uncaught, unframed.

Our senses, like guards in the tower, throw their restless beacon on some passing, possibly relevant thing, encircles it in a freezing beam, studies, moves on.

Some cry that inattention is getting worse, and much of the arts and media of our time either exploit or point this out.

Studies blame the world of social media and speedy video games for breaking down our patience and capacity to reflect, for nourishing us on sound bites.

But what’s the antidote?

Enter art.

Everything moves but some move more slowly, and some so slowly as to be imperceptible.

The very stillness and silence of certain pieces of art wants to draw you into a pocket, a well, a luxury of time – or is it a bewitchment away from time? They offer stillness as a gift, a portal if you will, into the world of the right brain – radiating, non-linear, revelatory.

Traditionally a still life painting was a formal rendering of non-moving things – crockery, wine bottles, dead animals, flowers, food, drapery — all consciously composed to marry or contrast shapes, colors, textures and lighting. It allowed the artist deep and lengthy observation and the subject did not get paid or laid, take breaks, or complain about a likeness.

But as Rice Polak Gallery Director Marla Rice points out, regardless of the subject matter all paintings and sculpture are still, and so serve the same purpose for a viewer.

The painting Mark Doty fell in love with at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York is a shadowy still life by Dutch artist Jan Davidsz de Heem, painted more than 360 years ago. This picture, no bigger than a school notebook he says, sparked a luminous treatise on time, love, memory, transience and the power of objects to retain them all.

Everything dissolves.

The objects in De Heem’s “Still Life with Oysters and Lemon” are fragile and fresh. Doty describes the “amber inch of wine” in a thick wineglass and “dewy grapes, curl of a lemon peel. Shimmery, barely solid bodies of oysters, shucked in order to allow their flesh to receive every ministration of light.”

Doty also said something simple about the nature of a still life that had never occurred to me: All of those glowing, moist things existed.

Beyond the cadmiums and cobalts, beyond varnish and brush strokes, the artist arranged these victuals, poured, peeled, shucked and afterwards probably consumed them. Maybe with his buddies.

They all existed more than 360 years ago, and are long, long gone.

Yet here they are at the MET still catching the brief and melting light, waiting for you to awaken. Them.

One study revealed that the average amount of time a museum or gallery visitor spends in front of a work of art is 4.5 seconds.

People pass but the art still stands, still, waiting with one simple purpose, to slow you down and pull you in — in time.